On the Founding of Schlarbhofen

1. The Danube-Swabian Colonization

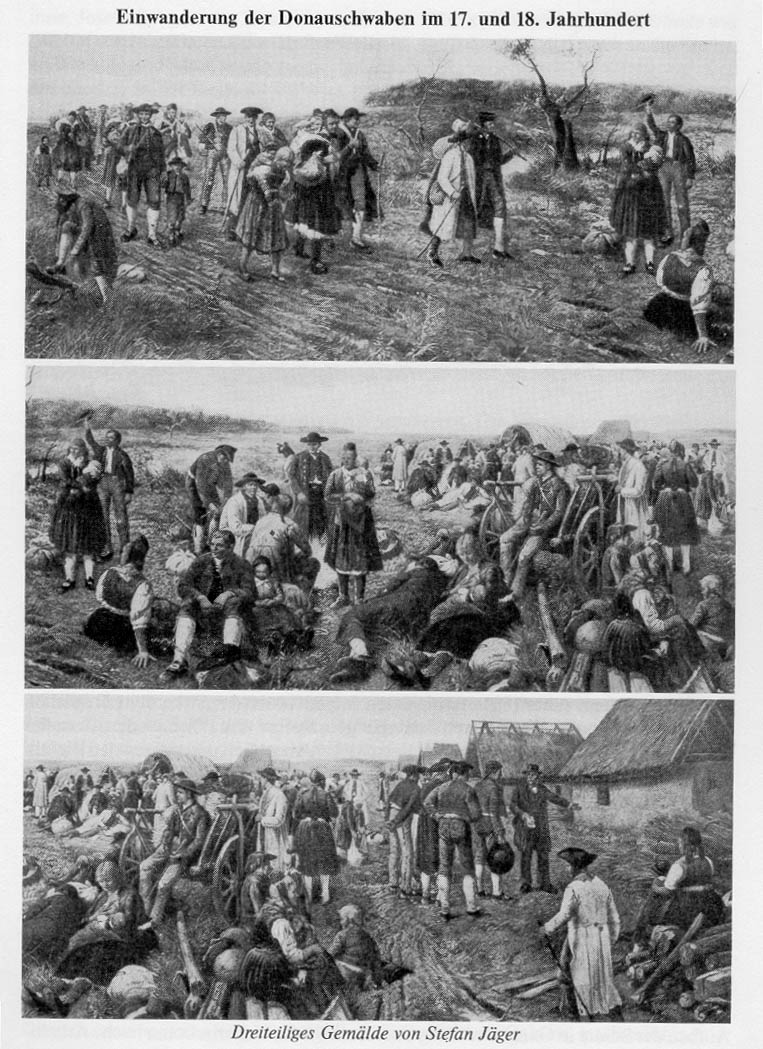

The fate of the Schlarb family in former Yugoslavia is typical for the Danube-Swabians in general. This ethnic group, unlike the Swabians found today largely in the German province of Baden-Wurttemberg, was not originally homogeneous; it possessed neither a distinct dialect nor area of origin. Rather it was composed of people emigrating from widespread areas of Germany, from the Palatinate, the Black Forest and as far away as Franconia and Bavaria. They settled in lands along the Danube belonging to the Hapsburg emperor, becoming in time an ethnic group with a distinct German dialect, their own customs and peasant dress.

The stage was set for this people movement by the Turk Wars during the 17th and 18th centuries. In the year 1683 the Turk general Kara Mustafa led his huge army in laying siege to Vienna, the climax of a westward military expedition lasting decades. Only with the aid of the Polish prince Jan III Sobieski was the Austrian Emperor Leopold I able to break the siege and repulse the Turkish army. During the following decades, imperial troops succeeded in driving back the Turkish occupants toward the southeast. After Hungary’s most important cities had been regained (Budapest 1686; Szeged 1687) and Belgrade liberated (1688), Prince Eugene of Savoy won a decisive victory over the Turks at Temisoara (1716). The Peace Treaty of Passarowitz in 1718 provided for the entire area north of Belgrade as far east as Transylvania, today eastern Hungary and northern Serbia or the Vojvodina, to be returned to the possession of the Austrian emperor.

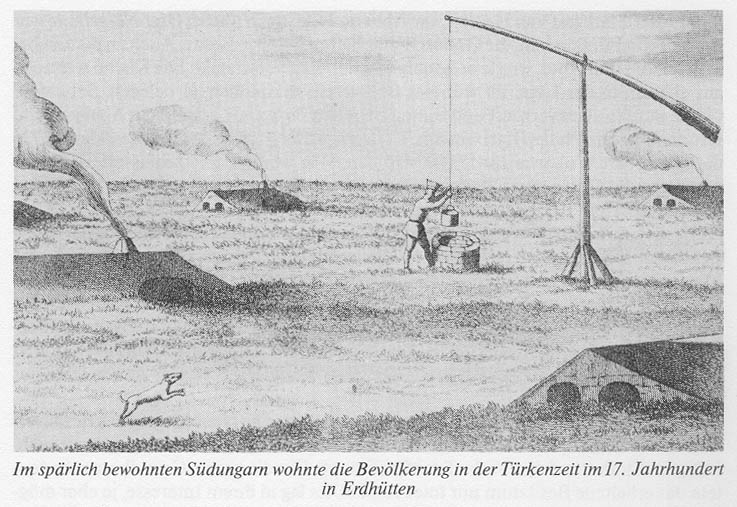

During the time of the Turks in the 17th century, southern Hungary was sparsely inhabited: the population lived in dugouts.

Wars and occupation had left behind a largely deserted and underdeveloped territory of paramount strategic importance. It was a matter of course to settle German peasants here from overpopulated areas of the realm in order that they build permanent settlements and farm the fertile river plains between the Danube, the Sava and the Tisza. Consequently, three so-called Swabian Movements were proclaimed in the course of the 18thcentury. First under Karl VI. (1711-1740), later Maria Theresia (1740-1780) and finally Joseph II. (1780-1790) settlers arrived from southwestern Germany (Alsace, Palatinate, Wurttemberg), from Bavaria and even as far away as France and Italy. Attracted by the prospects of temporary freedom from taxation, their own farming lands and material aid in settling, these largely destitute farmers colonized the southeastern frontier of the Hapsburg realm.

These colonization activities were generally well prepared. Each family was allocated enough land for raising crops and cattle and for building a house; cattle and farming implements were also provided. The new villages were laid out according to plan; every town had its own council, giving it a degree of autonomy in cultural matters. The fact that many of the settlers during the first movement died an early death is to be attributed to the wars and epidemics that ensued. During the early years of the 18th century, the Turks succeeded in crossing the Danube time and again, wiping out entire Danube-Swabian villages. Moreover, only the heartiest of the German colonists were equal to the swampy countryside and the hot summers. Frequent floods augmented the risk of disease. A rhyme commemorating those initial, difficult years was handed down and later often quoted by those returning to Germany, implicitly comparing their fate after the Second World War with that of their forefathers:

Die Ersten fanden den Tod,

die Zweiten die Not,

die Dritten erst Brot.

The first found death,

The second want,

Only the third bread.

By the third colonization period under Joseph II., the settlers had overcome the worst hardships in their new home.

Migration of the Danube-Swabians in the 17th and 18th centuries

Three-part paintings of Stefan Jäger

Religion played a central role in the lives of the German settlers. Villages were often laid out according to the religious affiliation of the new arrivals. For instance, a Roman-Catholic farming settlement would first have been established under Maria Theresia who required protestant immigrants to convert to the Catholic creed. Later, when Joseph II. expressly invited protestant colonists to come, a predominantly Lutheran village quarter would come into being. There were even cases in which Reformed Christians and Lutherans lived in separate settlements. One of the reason for this was that religious affiliation was an important consideration in making public appointments. While Calvinists (or Presbyterians) appointed their own minister, Catholics were obligated to accept their bishop’s choice of priests. Furthermore, the school teacher’s church affiliation was a matter concerning the entire village.

2. The Migration of Nikolaus Schlarb

The ancestors of the Yugoslavian Schlarbs originated in the Hunsrück, a hilly region located today in the German province of Rhineland-Palatinate. Toward the close of the 18th century, many peasants and poorer tradesmen from this area heeded the invitation of the Austrian emperor Joseph II., calling on them to settle in the Hapsburg crown lands on the south-eastern fringe of the monarchy. Among the colonists from the Palatinate participating in the so-called Third Swabian Movement was a certain Nikolaus Schlarb from the town of Bärenbach near Söhren. Motivated by the prospect of land and freedom, he and his family arrived in Siwatz (Sivac), a town now lying in the Serbian province of Vojvodina. In that day the area between the Danube and Tisza Rivers and north of Belgrade was known as the Batschka (Backa). Significantly, this Reformed Christian family chose to settle in Neusiwatz (New Siwatz), a newly founded farming community near the predominantly Catholic town of Siwatz. It is questionable whether Nikolaus Schlarb and his descendants went through the proverbial experience of “Tod und Not” (death and want, see above). For one thing, the community of Siwatz had been in existence for over 40 years; there would have been enough established settler families nearby to help them through the first winter. Even if he did not starve to death, according to family records Nikolaus Schlarb did die rather early, at the age of 64 on February 1, 1814. Like most of the Danube-Swabians he and his wife left behind a number of children. These in turn married and established their own farms and large families as well.

3. The Migration of Adam Schlarb

Statistics show that the Danube-Swabians in general experienced an appreciable growth in numbers during the 19th century. From the 30,000 odd German-speaking settlers in the Batschka, the territory in which Siwatz was located, in the 18th century arose some 150,000 by the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. There being little agricultural available nearby, Adam Schlarb, a great-grandson of Nikolaus Schlarb’s, decided to head south closer to the frontier of the empire and seek new land to settle.

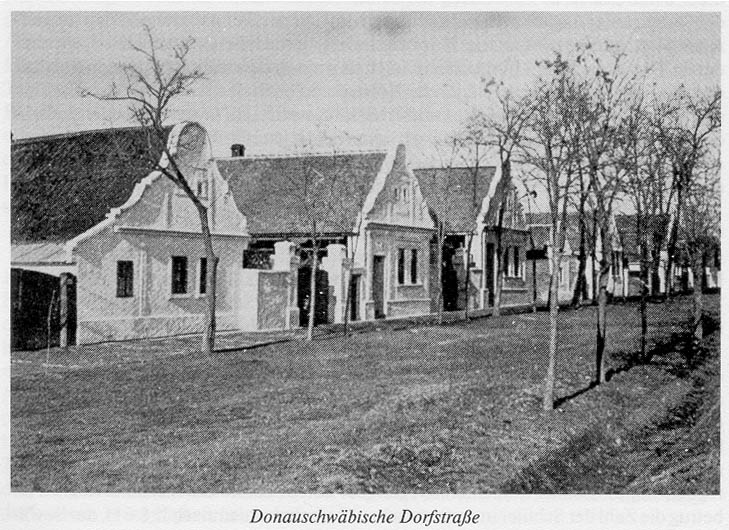

Danube-Swabian Village Street

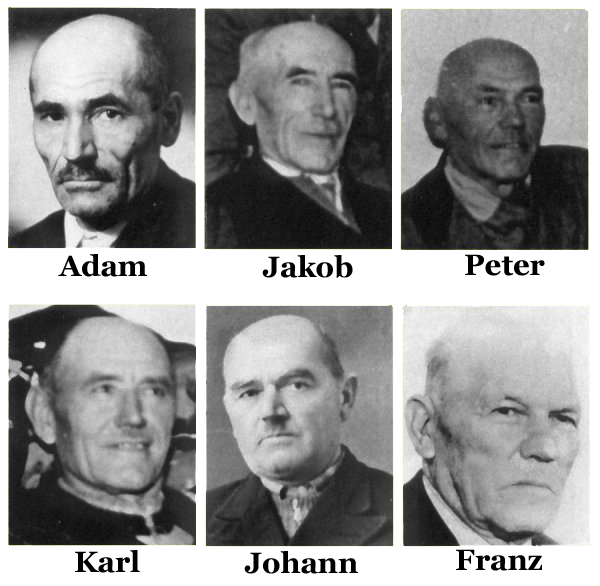

His first stop was the town of Dobanovci in the county of Zemun (Ger. Semlin, today in Serbia) where he married Katharina nee Waller in 1877. The newly-wed couple soon moved on to Rajevo Selo in Zupanja County in East Slavonia (today a part of Croatia) in order to begin a new life. Between the years 1883 and 1902 a sizeable number of children was born to this couple. These children would later become the founding generation of Schlarbhofen: Susanna (1883), Adam (1886), Jakob (1887), Theresia (1889), Christina (1890), Heinrich (1892), Peter (1894), Franz (1896), Karl (1898), Johann (1902).

In the predominantly Croatian town of Rajevo Selo the Schlarb family achieved a relatively high standard of living. Their sons not only possessed their own farms in time, they also controlled a number of small industries such as a grinding and a spinning mill for processing their agricultural goods.

Work on the farm dominated everyday life. On the one hand it was ruled by the order set forth by the change of seasons and the rhythm of planting and harvesting. Then too life was governed by the deep religious faith prevalent in the farming community. “Maintain order and order will maintain you” was the motto characterizing these rural residents’ lifestyle. Besides observing strict religious and moral customs, these people also enjoyed spirited celebrations such as weddings or the yearly “slaughter festival” (“Schlachte”). At slaughtering time the generations would assemble and butcher several pigs, making sausages and other meat products. The occasion was marked by special songs, lusty jokes, warm fellowship and opulent delicacies.

Like other Danube-Swabian farmers, the Schlarbs took little notice of events taking place beyond their village. Developments in faraway cities hardly touched them. Even the great political upheavals of the 19thcentury, such as in 1848 the March Revolution in Vienna and the Hungarian Rebellion only affected them to the extent that these events caused repercussions that later changed the lives of all German settlers under the Austrian monarchy. The Austro-Hungarian Compensation of 1867 brought on the one hand more rights and greater autonomy to the emperor’s Hungarian subjects in the one half of the monarchy. Yet the Danube-Swabians soon discovered that it meant for them the gradual loss of the special minority protection the Austrian emperor had promised to them at the time of settlement. Thus the Croatian language came to dominate in schools and public offices. German-speaking citizens of the empire such as the Schlarbs found themselves increasingly confronted with covert or even blatant discrimination.

In spite of this the Schlarbs continued to stress their German cultural identity. They always spoke German at home. As will be seen further below, this mindset of belonging to the international community of German peoples would, after the First World War and Slavonia’s entry into the new state of Yugoslavia, result in danger to the Schlarb clan and at the same time be their salvation.

4. The Demise of the Hapsburg Empire

When the Hapsburg empire crumbled, almost all of the formerly imperial nationalities strove for self-determination in the sense espoused by the United States president Woodrow Wilson. While the Serbs and Hungarians achieved their own national state, other nationalities such as Slovenians, Croatians, Bosnians and Kosovans, not to mention the German nationals in Yugoslavia, left the negotiating tables empty-handed. The roughshod manner in which national boundaries were established, while providing larger territories for political administration, sowed the seeds of discord that later, in the course of two wars, would bring forth a violent harvest in the form of expulsion, ethnic cleansing and mass murder. Rajevo Selo itself is, in fact, found at the approximate mid-point between Vukovar, Bjelijna, Tuzla and Bosanski Brod, an area in which not only thousands of German nationals were forced out of their homes and shot on river banks or executed in concentration camps, but also countless numbers of Bosnian Moslems, Croatians and Serbs.

5. The Rise of National-Socialism

Even though they remained conscious of their German identity, the Yugoslavian Schlarbs, like other Danube-Swabian families, did not openly adhere to National-Socialist ideology. On the contrary, while cheering Hitler’s measures to advance German cultural values, they could hardly identify themselves with the political goals of the National-Socialist Party. The Danube-Swabians were basically concerned with devoting themselves in peace to farming in the country which in the meantime had become their home. Even in the young country of Yugoslavia they merely wished to be and remain Germans. This attitude is conveyed by a Danube-Swabian newspaper commentary in the 1930’s:

To us, National Socialism is a political party, no more and no less. Yet the party is not synonymous with the people from which we have descended, and the party leaders are not synonymous with Germany. In our thinking there was a German people before this party appeared on the scene and there will continue to be a Germany even after this regime has taken its place in history.

(Adam Berenz, Die Donau, No. 8/1937, quoted in: J. V. Senz, Geschichte der Donauschwaben [History of the Danube-Swabians], Munich 1993, p. 220)

In just a few years this prophecy would fulfill itself for the Schlarb family.

In the year 1937 the National-Socialist government in Berlin established the Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle (Bureau for German National Resources). This office was given the task of supporting the many German nationals outside of the so-called Vaterland (i.e. territorial Germany) by organizing them and supporting their activities. The ranks of the German nationals included not only Danube-Swabians but also Germans in the Sudetenland (Bohemia), Silesia (Poland) and East Prussia (Poland/Soviet Union). The Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle, or VOMI for short, intervened for the German nationals in Yugoslavia during World War II – even against the latters’ best interests at times. When Serbian officers staged a coup d’etat against the government in Belgrade in March 1941, German troops overran all of Yugoslavia, establishing soon after a Croatian government in Zagreb. Members of the Schlarb family depict these events from their perspective:

The German inhabitants of the village [Rajevo Selo] were observed by the authorities after the coup in Belgrade (March 27, 1941). Four leading men were kept as hostages in the town hall while the rest of the residents were not allowed to leave town. All of the men conscripted to military service when the Yugoslavian army mobilized complied with the order. Most of them, however, did not see action. The Yugoslavian soldiers who returned were not disarmed and there were no acts of sabotage.

(Danube-Swabian Cultural Foundation, Weißbuch der Deutschen aus Jugoslawien [White Book of the Germans in Yugoslavia], Munich 1992, pp. 758f., abbr. Weißbuch in the following)

From this it is evident that the Schlarbs too behaved as loyal Yugoslavian citizens until the German invasion.

With the aid of the VOMI, the German nationals in Yugoslavia were recognized as a legal body for the first time in their history. Moreover, behind the scenes the VOMI was working on putting Hitler’s secret plan into action of repatriating the Danube-Swabians into the German Reich. Like all others, the Schlarb family had no idea of this intention and they would not have agreed to it had they known. This was one of the reasons why the Evacuation Order of 1944 caught them completely unprepared.

6. Germany Invades Yugoslavia

After the German invasion of Yugoslavia in 1941 the country was far from at peace. On the one hand, in Croatia the so-called “Ustasha” (“rebels”) were terrorizing the Serbian-Orthodox citizens, forcing them to convert to the Roman-Catholic creed. At the same time, in Serbia communist partisan guerrilla cells under Tito’s leadership were gathering strength, taking their place beside the Serbian-nationalist Chetniks, yet another paramilitary organization. This situation amounted to all-out civil war. The more the Ustascha threatened the Croatian Serbs, the more these Serbs crossed the border to join the communist partisans. Even though the partisans abjured Serbian Orthodoxy, their communist, panslavist ideology propagated a vision of all Slavic peoples living together in equality in a new socialist state.

Due to their impartial stance, the Rajevo Selo Schlarbs remained largely unharassed by the various Yugoslavian underground fighting groups:

“The Ustasha threatened the Serbs, they forced them to be rebaptized into the Catholic faith and they wanted to tear down the Serbian church. That I was able to hinder,” Jakob Schlarb recalls. “For this the Chetniks, whose local command was stationed in Vucilovac on the other side of the Sava, were indebted to me. That was one of the main reasons why we were never threatened by the partisans during the entire course of the war.”

(Weißbuch, p. 759)

Yet, in the end, impartiality helped the Schlarb family as little as it did all other German nationals in Yugolslavia. Despite the Danube-Swabians’ loyalty to the state of Yugoslavia prior to 1941, Serbian and Croatian politicians had already determined to purge the country of every trace of German presence. This determination hardened when Danube-Swabian soldiers entered the service of the German Reich. Young men of the Schlarb family were among those who performed military service for Nazi-Germany in wartime. Initially the German nationals established only a self-defence corps in order to protect their villages from partisan attacks. Yet at the express command of SS Fuehrer Himmler this corps was developed into an entire division named “Prinz Eugen” and composed only of German national troops. Accordingly to law only “Reichsdeutsche”, i.e. Germans born in territorial Germany, were allowed to enter the regular German army, the Wehrmacht. Thus, the German national division was placed under the direct command of the SS as part of the so-called “Waffen-SS” (“Combat SS”). Even though German nationals were officially not obliged to do military service, there is more than enough evidence pointing to the fact that the Schlarbs and others were subject to de facto conscription. Among other evidence, this is made clear by a letter that Himmler wrote to the VOMI in 1942:

I ask you to inform Janko [the leader of the German nationals] orally about the following: I as the one appointed by the fuehrer to be responsible for German nationals all over the world have ordered this ethnic group to be conscripted. It is only for reasons of foreign policy that we have refrained from publishing this declaration… It is intolerable that Germans sit around somewhere in Europe as pacifists, allowing themselves to be protected by our battalions.

(Weißbuch, p. 79)

For this reason, after World War II certain members of the Schlarb family had to bear the stigma of having belonged to the SS. The individuals themselves knew that they had had no other choice. Nonetheless it was, and still is, all but impossible for them to explain these circumstances to friends, neighbours and colleagues in their new home countries, in Germany, Canada or the United States.

7. The End of World War II

With the German defeat at Stalingrad in February 1943 and the Allied invasion of the Normandy coast in 1944, the German combat fronts on both sides began to crumble rapidly. It was only a matter of time before German nationals in Yugoslavia would be exposed to attacks by the Soviet Red Army and the Yugoslavian partisans. In the Serbian Banat it became apparent relatively early that the German nationals had more to fear from the partisans. While the Red Army merely arrested town leaders and other individuals in politically responsible positions, the partisans wanted payment in blood for the German occupation of Yugoslavia and sought to eradicate all traces of German presence there. The brutality practised by the partisans was, incidentally, also typical of the later Yugoslavian Wars 1991-1999. This type of warfare may be understood as a cultural relict of the longstanding Turkish occupation:

The exceptional brutality of Balkan warfare was not a phenomenon unique to the last war [i.e. World War II]… The history of war on the Balkan peninsula is at once a history of awful brutality, of plundering, arson and rape. It is largely the influence of Turkish rule that is still at work here. The concept of the “sacredness” of human life was thoroughly foreign to Turkish warriors; Islam espouses wiping out all unbelievers. Thus, during their conquests the Turks destroyed towns and villages, slew women and men, enslaved young women and girls and executed enemy soldiers. In fighting the Turks, their oppressors, the Balkan peoples developed similar methods.

(G. Scheller, quoted in: G. Böddeker, Die Flüchtlinge, Die Vertreibung der Deutschen aus dem Osten [The Refugees, The German Expulsion from the East], Munich 19955, p. 342)

8. Uncertain Refugees Flee to the West

As early as September 1944 Danube-Swabian refugees from the Romanian Banat, fleeing the Red Army, passed through Slavonia. Yet the VOMI with its headquarters in Berlin, responsible for the evacuation of German nationals, had no clear view of what was transpiring. On the hand it was thought that the German army would repel the Soviets at the border of Yugoslavia and Romania. Then too, Hitler ordered all German nationals to remain where they were so as not to weaken combat morale. Even though Hitler originally had planned to relocate the Danube-Swabians in other territories of the Reich, this vision did not prove compatible with the impromptu strategy developed in the latter months of the war, one of holding out and waiting for salvation by the Wunderwaffe, the wonder weapon.

For this reason the German nationals were fraught with uncertainty up to the very last. The older ones, on the one hand, were prone to stay since they felt relatively safe. After all, they had survived unharmed the transition from the Hapsburg monarchy to the young monarchical republic of Yugoslavia. Younger people, on the other hand, particularly those with higher education, perceived the approaching danger, yet they too were not permitted to flee to the west. Some, among them members of the Schlarb family, fled anyway, crossing the Austrian border in secret and taking up clandestine residence in that country. The young men in the Prinz Eugen Division had no choice, of course; to attempt returning home meant death as a deserter in front of a firing-squad.

It was October 2, 1944 by the time the order prohibiting flight was revoked; the Red Army had already advanced far into the Serbian Banat. Thus, in this area, roughly 150 kilometres away from Rajevo Selo, only 10 percent of the population could be evacuated. The way was now clear for German national officials to organize and carry out a general evacuation. In East Slavonia this proved successful despite time being short, as Jakob Schlarb’s account relates:

The evacuation was organized by the county authorities in Vinkovci. Wagons from the towns of Rajevo Selo, Gunja, Racinovici and Drenovci assembled in Rajevo Selo, the town of Vrbanja joined us in Zupanja. I acted as leader of the trek and my brother Franz helped me. The trek involved 350 wagons and some 1000 people. We marched toward Esseg, from there across the Drava, through Hungary and near Sopron we crossed the border.

(Weißbuch, p. 759)

In the trains there was room for only a few of the elderly and ailing. Most of the refugees formed a trek, a convoy of horse-drawn wagons carrying mothers, little children and the aged, the more able walking alongside. Thankful for just being able to keep the family together, they had room for only the barest necessities. Tarpaulins were stretched over the wagons to protect the travellers from wind and rain and sometimes they even served as tents:

Every evening some began to worry about where we were going to stay for the night. I was often asked: “Cousin Jakob, how much farther are we going to travel?” I answered: “Well, much farther.” We camped on the road, regardless of rain, storms and wind. Our poor, meek horses shuddered in the cold, the children cried and the elderly with them.

(Weißbuch, p. 759)

The refugee trek led by Jakob Schlarb left Rajevo Selo on October 14, 1944. Four days later, on October 18, they crossed the border to Hungary in Osijek (Ger. Esseg). Now they had formally arrived in the German Reich and were thus in tentative safety. The daily challenge of finding food for all, including the horses, and the search for nightly quarters were to accompany them for many days to come. The aged in particular suffered under these severe conditions and some of them died along the way. The trek reached its next major milestone on November 2: on this day they passed through Sopron (Ger. Ödenburg) in western Hungary:

Six kilometres past Sopron came the border. After that we traveled through German villages.

(Eva Jason nee Schlarb, Chronicle Manuscript 1948-1952; abbr. Chronicle in the following)

The Schlarb family did not, of course, pass through German but rather Austrian villages during those days in November 1944. Even so, the people here spoke German and the refugees were able to make themselves more easily understood. Beyond this they were cheered by the unspoken expectation that among “Germans” they would be better able to cope with their lot as refugees. Yet such hopes were soon scattered. Austria itself had suffered much during the war: cities had been bombed out, food was being rationed, need and hunger were the order of the day. To the Austrians, the refugees from the east simply represented added pressure on an already decrepit economy.

The cold nights gradually became a real problem:

“Near Ebenfurth we divided the trek into two parts in order the make it easier to find quarters for the night”. (Chronicle).

They were overjoyed when in St. Pölten, 40 kilometres west of Vienna, they were put up in a house.

9. Where to now?

Where to now? The question had become more and more acute once they had crossed the Austrian border. After all, the Schlarb family had been in Yugoslavia for over 150 years, neither in Austria nor in Germany did they have any more close relatives. A grandson of Adam Schlarb’s, Jakob junior, had already moved with his family to Neumarkt-Kallham, a town in Upper Austria near Grieskirchen, where they had found work and quarters. It was quite natural to seek out this place and reunite the clan.

In Neumarkt-Kallham they were met with a less than warm welcome:

We thought we had arrived at the end of our journey. However, this was not the case. One after the other the farmers came out of their houses and examined us warily. After thinking things over for three hours, they assigned us apartments. For 10 people we were given one small room.

(Chronicle)

Two days later the farmers Josef Kirnbauer and Josef Rebhan put the Schlarbs up in roomier quarters in a part of town known as Holzleiten. There they stayed for a year and a half, until August 1946. They laboured for the farmers during these months, receiving food for their efforts in the fields. In this way their lot became no worse than that of the average Austrian at war’s end. The only difference was that they had lost everything: they had been reduced from prosperous farmers to sharecroppers.

Barely a month after arriving in Neumarkt-Kallham, on December 16, 1944, the head of the clan, Adam Schlarb, died. At the age of 88 he had already been in fragile shape in Yugoslavia; weakened from the ordeals of the journey, he did not grow accustomed to the unfamiliar new setting. He was never to see his sons, daughters and grandchildren rise from their defeat.

10. Genocide of the Danube-Swabians

What had happened in the meantime to those few German nationals in Rajevo Selo who had not joined the westward trek? Jakob Schlarb gives a few details on this:

15 people, mostly in mixed marriages, remained in the village. At first things stayed quiet in the village when the partisans marched in. About two months later all of the Germans were rounded up at night, “four of them were liquidated and sent floating down the Sava; another was tortured half to death and died shortly thereafter. Four of them were sent to the camp at Mitrovica where one of them died. The other three were sent home after three years imprisonment and were then observed by the Milicija [civil police].”

(Weißbuch, p. 759)

Later the Enquiry Commission of the German federal government found out that the partisan groups had methodically committed genocide against the remaining Danube-Swabians. Partisan execution squads moved from village to village, arresting the German nationals and then shooting a number, among them women and children. Approximately 10,000 German nationals, mostly well-to-do or leading individuals, were put to death between October 1944 and April 1945 during the so-called Aktion Intelligenzija ordered by Tito. In the course of the year 1945 most of the survivors were dispossessed and placed in concentration camps where they did forced labour. A total of 150,000 Danube-Swabians were transported to Russia where over 20 percent of them died in the years following due to inhuman living conditions. The Soviet government had insisted on large contingents of German nationals as forced labourers to make restitution for the damage done by the German army during the war. Not until the early 50’s were those remaining in Yugoslavia allowed to emigrate to the German Federal Republic. At the same time, thousands of Danube-Swabians families were forced to relinquish their children. These children were taken away from their parents to be raised as Yugoslavian citizens. All totalled, approximately 69,000 German nationals died in Yugoslavia from the time the Red Army invaded the country until peace was finally established.

11. The Return to Germany

It is an irony of history that the Schlarb family returned to Germany in the same condition as when they had left, as poor, landless farmers. On August 8, 1946 the Schlarbs began a long train journey that would take them to their next tentative home. Together with hundreds of other refugees, they traveled by way of Attnang-Puchheim, Salzburg and Nuremberg to Windsheim in central Franconia, a district in Bavaria. In the village of Rodheim in Uffenheim County they were allotted new quarters, larger than the last, along with the means for farming on a very small scale. Their initial modest success made them hope for more: after buying two pigs, they were even able to afford a cow. Gradually they again began to see themselves as independent farmers.

Germany was in a sorry state in the years immediately following the Second World War. The larger cities were literally choking in rubble and ashes; industrial production was at an all-time low; and, to make matters worse, 12.5 million refugees had swamped the country and were begging to be fed and put up. Not only were there Danube-Swabians, but also German nationals from Sudetenland, Silesia, East and West Prussia. When word of a new law regulating the settlement of refugees reached Rodheim, the Schlarbs decided to take matters into their own hands:

Jakob Schlarb senior travelled constantly, establishing contacts to the Bavarian state government. Thanks to him the so-called Pangerfilze [Pang Moor] was offered to the Schlarb clan as an area for cultivation and settlement.

(Chronicle)

12. The “Dream” of Schlarbhofen

Not every farmer dreams of being given moorland to work. This type of land requires skill in hydrological techniques on the one hand as well as intensive labour on the other. The Schlarb family accepted the challenge even though their neighbours near the heath regarded their efforts skeptically at first. Significantly, two other moors border on Schlarbhofen, the Hochrunstfilze and the Kollerfilze; no one has ever gone to the trouble of cultivating either of these.

This clan of farmers had three particular advantages when they took on the 145 hectares of moorland. First, they had large labour reserves to drawn on. Six of Adam’s sons had survived the war. These in turn had their own families, some of them with grown-up children. In all, there were about 50 people of working age. Beyond this, they brought with them age-old knowledge derived from working moors and swamps on the Danube and Sava Rivers in Yugoslavia. Finally, they got help from experts: the Moorwirschaftstelle Großkarolinenfeld, an initiative founded by Palatine settlers for cultivating another moor, provided advice as well as specialized machinery.

Schlarb brothers

Work at the Pangerfilze began on June 15, 1948. Cultivation efforts had to wait though, first living space for 71 people was required:

Three barracks are being torn down at the air field in Bad Aibling. We have to work carefully in order to be able to reassemble them later as living barracks.

(Chronicle)

The barracks and the first field

The moorland was originally covered with trees and bushes. Two months later an area had been cleared and the framework of the barracks erected. The outside walls of the barracks were then insulated with clay while brick walls were erected in the interior to create separate dwellings for each of the families. By the beginning of October the barracks were finished and the rest of the fields could be cleared. The first ploughing was done before the onset of winter, revealing the dark, loamy moorland soil.

Clearing the land

Redistributing the soil

Laying the tracks

Now rapid progress is made. The entire winter is devoted to draining the cleared fields. As long as daylight allows, the main drainage canals are dug, mostly by hand. The men lay tracks to the ditches, from there women and men push mining carts full of dirt to fill the deeper areas of the moorland. By laying 70 kilometres of clay tiles underground, the workers create a huge drainage system. The first crops arrive with the spring: moorland potatoes are ready for harvesting. Varieties of crops are planted in following months and years; along with wheat, corn and other types of grain, hemp does well in the black soil. It is not long before these 70 odd people are able to live exclusively off the land. Beyond this, by selling their products they are able to accumulate cash which is converted in time into horses, cows and pigs as well as tractors and other farming machinery. On May 15, 1952, not quite four years after setting foot on the Pangerfilze the first time, the Schlarbs set the cornerstone for the first of a number of farmhouses.

13. The Visit of Horst Mönnich

A writer from Hamburg by the name of Horst Mönnich visited Schlarbhofen in the early 50’s. From his impressions and research work he went on to write a radio play entitled Hiob im Moor (Job in the Moor). The choice of titles was obviously no coincidence as he endeavoured to point out parallels between the plagued figure from the Bible and Jakob Schlarb senior who had suffered great loss during the events of the war. There are indeed striking similarities between the two: Job, on the one hand, unexpectedly loses his family and riches; Jakob, on the other, had to forsake his possessions, property and home overnight. The biblical Job is tempted by Satan to curse God and thus achieve satisfaction; moreover, it was enticing to Jakob and his siblings to capitulate and resign themselves to their fate as refugees, as indeed millions of others did. With few exceptions this meant being scattered over all of Germany, dwelling in bombed-out basements or back alleys in the cities, foraging for work and waiting for times to get better. It was a matter of course that the former refugees were assimilated into the general population. They became industrial workers or tradesmen, erecting their modest houses in the suburbs, mostly with their own labour.

The Schlarb Family of Rajevo Selo resisted fate, they stayed together and they stayed in the country. Yet even amidst the success story of the first generation back in Germany they were aware that for most of them Schlarbhofen could only serve as a temporary home. 145 hectares of land was almost too little even for the 70 pioneers from Yugoslavia. The playwrite Mönnich expresses it in this way:

Narrator: …brushing a tear from his eye, Jakob Schlarb brought his son Martin to the train, and this train travelled to Bremen, and from there a ship left for Canada.

First Voice: Martin, the youngest, emigrated, hiring on at the nickel mines of Toronto in order to earn dollars…

Narrator: Yet now Eva, Martin’s sister, could afford to study to become a translator.

Jakob: The moor is too small for all of us, Eva. You have what it takes to study. This shall be your home. But you can earn your bread better and more easily out there.

(Horst Mönnich, Hiob im Moor, Hamburg 1966, p. 73)

14. Schlarbhofen and Beyond

The six Schlarb brothers, that is Adam’s sons, and their wives were to spend the rest of their lives in Schlarbhofen.

They held on to the customs, the Danube-Swabian dialect and the protestant faith they had brought with them from Yugoslavia. Even though some of them spent almost half their lives in Bavaria, they never became Bavarians; their neighbours could not accept them as such and they themselves would not hear of it anyway. But their children were already moving on, some to Kolbermoor, the small town nearby, and others, like four of Jakob’s children, emigrated to faraway Canada.

Adam’s sons and the geese (photo courtesy of Matthais Schlarb)

This tendency became even stronger among the third generation, that is, those born around the time Schlarbhofen was founded and thereafter. Only few of them could expect to take over their parents’ farms and even fewer wanted to spend their whole lives working on a farm. During the 60’s and 70’s, when the European Economic Community’s agricultural policy began to take hold, it became increasingly difficult to make a small farm pay: premiums were paid for fallow fields; it made more sense to collect compensation payments than to sell milk. Those of the younger generation learned vocations or attended university and moved to Rosenheim or Munich. They, Adam’s great-grandchildren, were the first for whom the hot summer days on the Sava River were not even a distant memory; to them, the Danube-Swabian world had become immersed in history. Today, all of them speak Bavarian dialect, some have become Roman-Catholics, nothing in their lifestyle distinguishes them from their neighbours. Only occasionally, at a wedding, a funeral or some other family event, they regress into the old “schwowische” (Swabian) habits of speech; then they talk about the early years, when their elders were still alive and Schlarbhofen was little more than a wilderness.

Schlarbhofen today

Responsible for content: Robert Schlarb, Graz, Austria

Photo sources: Katharina Stieb nee Schlarb; Werner Stieb;

J. V. Senz, Geschichte der Donauschwaben, Munich 1993;

Donauschwäbische Kulturstiftung, Weißbuch der Deutschen aus Jugoslawien, Munich 1992 (maps); www.mapquest.com (maps)

© 2000 by Robert Schlarb, Graz, Austria

About the Author

Writer, historian, translator, interpreter – born in Ottawa, Canada, a son of German nationals, Robert-Phillip Schlarb BSc MA MTh PhD became a citizen of Austria in 1995. 100% fluent in English and German, he works as a freelance translator specializing in PC programming, network technology, religion, theology, philosophy, psychology, social sciences, mechanical engineering, natural sciences, and legal contracts (esp. corporate).

Writer, historian, translator, interpreter – born in Ottawa, Canada, a son of German nationals, Robert-Phillip Schlarb BSc MA MTh PhD became a citizen of Austria in 1995. 100% fluent in English and German, he works as a freelance translator specializing in PC programming, network technology, religion, theology, philosophy, psychology, social sciences, mechanical engineering, natural sciences, and legal contracts (esp. corporate).

Directions to Schlarbhofen

Dear Phil,

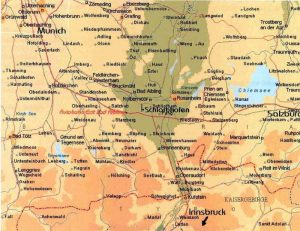

I was referred to you by my brother, Henry Schlarb of Ottawa Canada. He tells me you are planning a trip to Germany this coming summer and would like to visit Schlarbhofen. As you can see I am including a map to help you get there since the place is not included in most maps.

Here is how to get there (from Munich/München):

Follow the A8 (Autobahn München – Salzburg) until the exit Bad Aibling and go about one kilometer to the village of Pullach where you reach the provincial highway from Munich to Rosenheim. Here you head east (turn left) in the direction of Kolbermoor and Rosenheim and keep going about three or four kilometers. Here comes the difficult part: On your right you will see basically farms and fields with the mountains in the background. After one such field you should come across a used car lot on the right hand side and you may notice a small sign saying “Schlarbhofen”. This is Schlarbhofenerstrasse and you turn right here and continue on straight ahead for about one kilometer. Once you reach a cluster of buildings you are there.

I don’t know what you have heard up to now, but don’t expect a whole lot. The village is basically a former farming settlement. Now it houses a number of people who commute to Rosenheim and Munich for work. If you need further information and would like to announce you are coming, get in touch with my cousin Werner und Sylvia Stieb.

Feel free to get in touch with me any time. I live in Austria near Vienna, about a four hour drive from Schlarbhofen and know about as much about the family history as anyone alive.

Robert Schlarb